| Somalisch und Arabisch

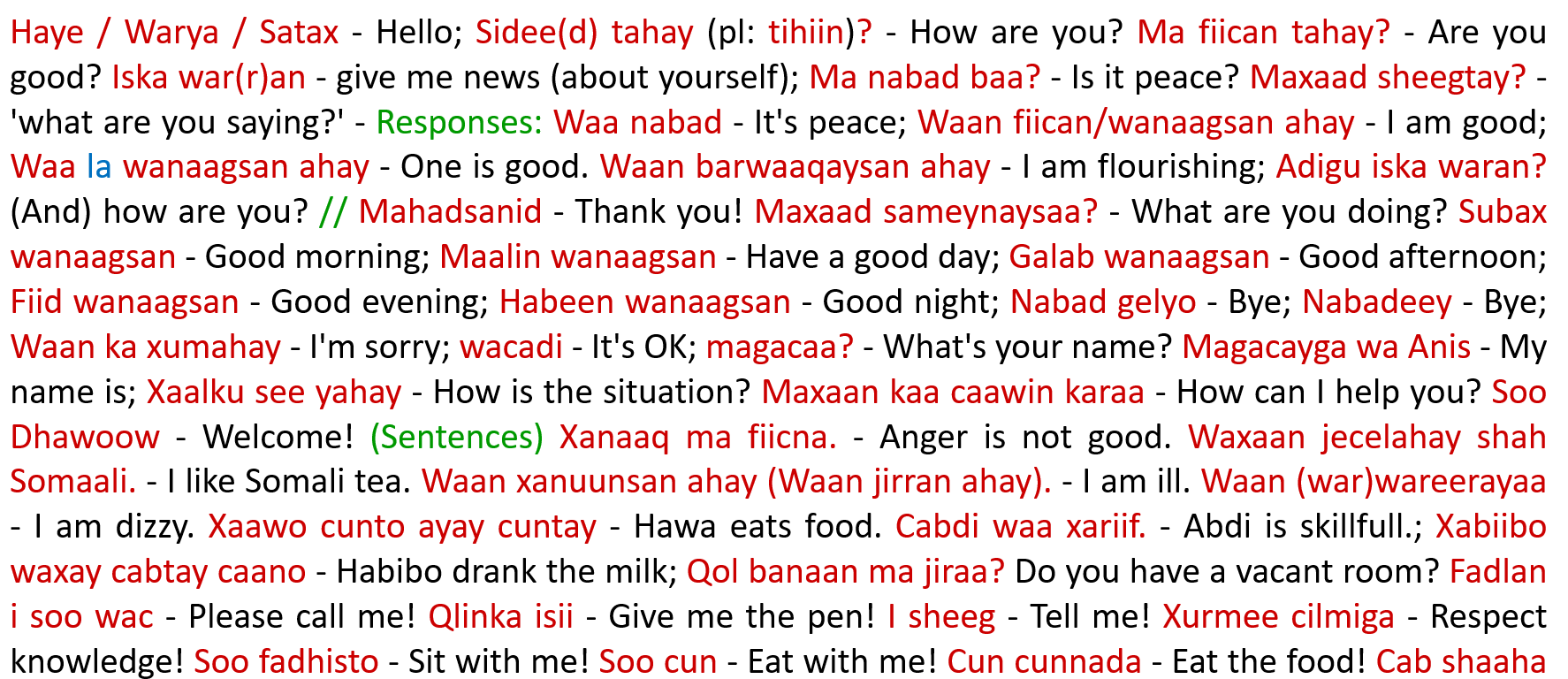

Somalisch ist mit ungefähr 12 Millionen Sprechern die bekannteste kuschitische Sprache vor Oromo und Afar. Es handelt sich dabei um die östlichste Untereinheit der afro-asiatischen Sprachfamilie. Zu dieser Famlie gehören die meisten Sprachen des nördlichen Afrikas, vom Mittelmeer bis zur Sahara. Mit der semitischen Sprache Arabisch ist sie nicht verwandt, doch stehen diese beiden Sprachen schon lange in einer engen Beziehung zueinander. Die Somalis haben aufgrund ihrer geografischen Lage sehr früh den Islam kennengelernt – Mekka an der Wasserstraße des Roten Meers ist nicht weit vom Norden des Landes entfernt. Der starke gesellschaftliche und sprachliche Einfluss entwickelte sich aber wohl erst nach dem Jahr 1000 mit dem Handel. Die Händler und Patriarchen brachten eine Fülle von Fremdwörtern in diese wie auch in Dutzende andere Sprachen. Auf dem Minilexikon-Ausschnitt oben lassen sich z.B. folgende arabische Wörter identifizieren:

waalid والِد (Vater), wadani vielleicht von وَطَن (Heimat), wakhti وَقْت (Zeit), shay شَيء (Ding), warqad وَرَقة (Blatt Papier), wasaq وَسَخ (schmutzig), wasiir وَزير, weji وَجْه (Gesicht), welwel وَلْوَلة (Wehgeschrei), wershed وَرْشة (Werkstatt), wicid vielleicht von وَعْد (Versprechen), saaxiib صاحِب (Besitzer; Freund)

Vielleicht ist auch shaqayn aus dem Arabischen, zumindest gibt es ein Verb شَقَّ (schaq-qa), das „mühevoll sein“ bedeutet. Es könnte aber auch eine sehr sehr alte Verbindung sein, dieses Gefühl hatte ich bei manchen Wörtern. Immerhin hat das Somalische den seltenen Kehllaut ع und schreibt ihn grafisch angelehnt als c. Auch die seltenen Kehllaute ق (q) und ح (x) gehören zu beiden Alphabeten. (Somalisch hat übrigens auch ein dh, dass wie ein indisches d klingt, mit der Zungenspitze am oberen Gaumen.)

Heutzutage ist das Arabische neben Englisch die wichtigste Fremdsprache für Somalis. Als Flüchtlingshelfer zwischen 2015 und 2017 habe ich einige Dutzend Somalier kennengelernt und mindestens die Hälfte davon konnte sich auf Arabisch verständlich machen und auch Gespräche führen. Anders hätte ich gar keinen Zugang gefunden. Diese Bedeutung der arabischen Sprache lässt sich nicht allein mit dem Islam erklären, zumindest nicht primär. Es ist eher so, dass es sich gehört, ein wenig Arabisch zu können, bzw. dass es normal ist.

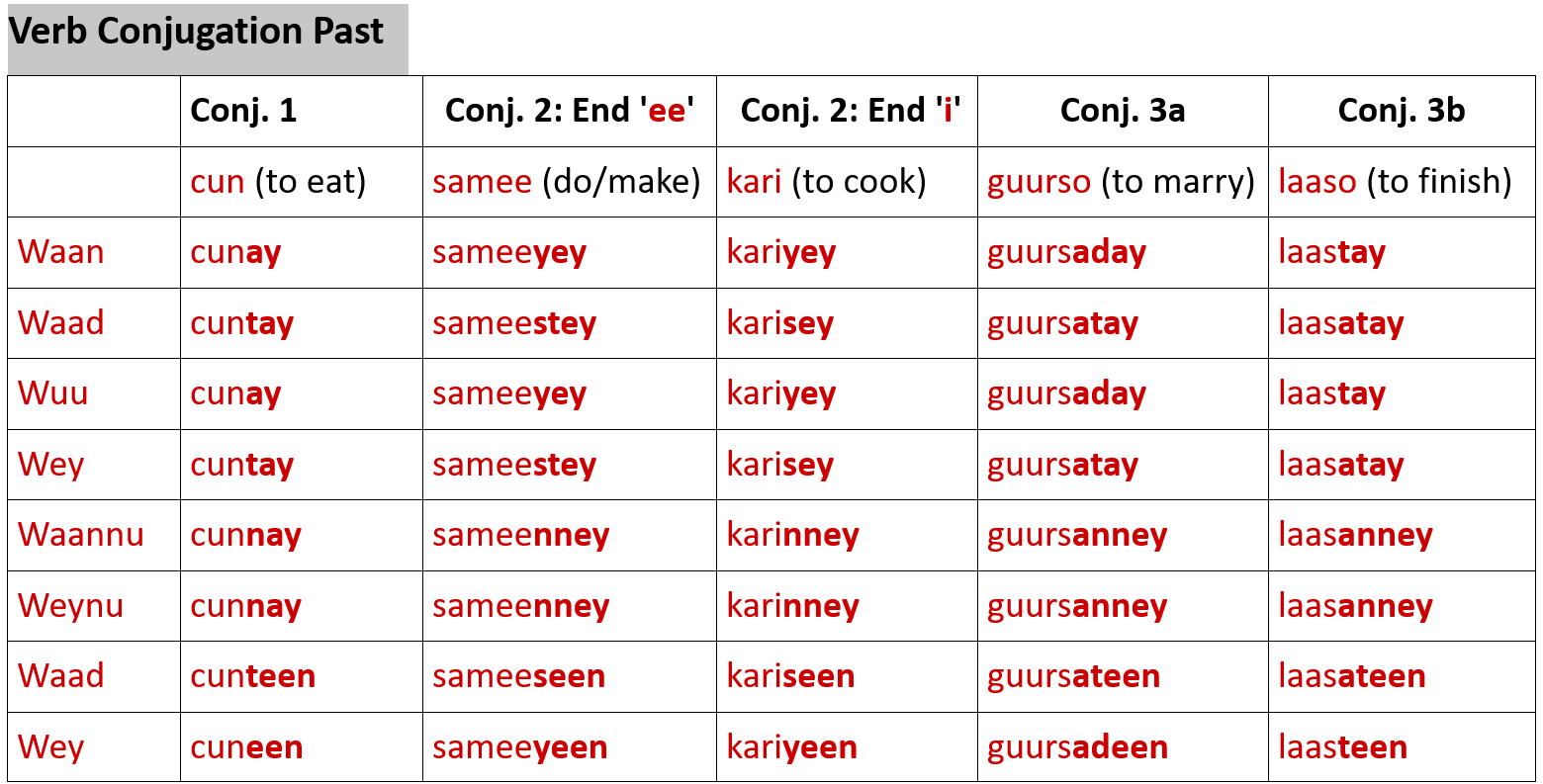

Zu den eigentümlichen Parallelen gehören auch die häufigen Verben yimi (kommen) und odho (sagen), denn sie werden in der Vergangenheit arabisch konjugiert, im ersten Fall: imid, timid, yimid/timid und im Plural nimid, timaaddeen und yimaaddeen. Vergleiche dies mit der Präsens-Konjugation eines arabischen Verbs, z.B. kataba (schreiben): aktubu, taktubu, yaktubu/taktubu und im Plural naktubu, taktubuuna und yaktubuuna. Das ist höchst ungewöhnlich. Diese Verben sind Ausnahmen, die Konjugationstabelle für regelmäßige Verben sieht so aus: |

Somali and Arabic

Somali is the best-known Cushitic language, ahead of Oromo and Afar, with about 12 million speakers. It is the easternmost subunit of the Afro-Asiatic language family. This family includes most of the languages of northern Africa, from the Mediterranean to the Sahara. It is not related to the Semitic language Arabic, but these two languages have long been closely related. Because of their geographical location, Somalis were introduced to Islam very early – Mecca on the Red Sea waterway is not far from the north of the country. However, the strong social and linguistic influence probably developed after the year 1000 with trade. The merchants and patriarchs brought a wealth of foreign words into this language as well as dozens of others. On the minilexicon excerpt above, for example, the following Arabic words can be identified:

waalid والِد (father), wadani perhaps from وَطَن (homeland), wakhti وَقْت (time), shay شَيء (thing), warqad وَرَقة (sheet of paper), wasaq وَسَخ (dirty), wasiir وَزير, weji وَجْه (face), welwel وَلْوَلة (wail), wershed وَرْشة (workshop), wicid perhaps from وَعْد (promise), saaxiib صاحِب (owner; friend)

Perhaps shaqayn is also from Arabic, at least there is a verb شَقَّ (shaq-qa) meaning "to be laborious". But it could also be a very very old connection, I had this feeling about some words. After all, Somali has the rare guttural sound ع and writes it graphically aligned as c. Also, the rare guttural ق (q) and ح (x) belong to both alphabets. (Somali, by the way, also has a dh that sounds like an Indian d, with the tip of the tongue on the upper palate).

Today, Arabic is the most important foreign language for Somalis, along with English. As a refugee aid worker between 2015 and 2017, I met a few dozen Somalis and at least half of them could make themselves understood and also hold conversations in Arabic. I would not have found access otherwise. This importance of the Arabic language cannot be explained by Islam alone, at least not primarily. Rather, it is a matter of education to know a little Arabic, or rather, it is normal.

Among the peculiar parallels are the common verbs yimi (to come) and odho (to say), because they are conjugated in the Arabic past tense, in the first case: imid, timid, yimid/timid and in the plural nimid, timaaddeen and yimaaddeen. Compare this with the present tense conjugation of an Arabic verb, e.g. kataba (to write): aktubu, taktubu, yaktubu/taktubu and in the plural naktubu, taktubuuna and yaktubuuna. This is highly unusual. These verbs are exceptions; the conjugation table for regular verbs looks like this: |